|

||

|---|---|---|

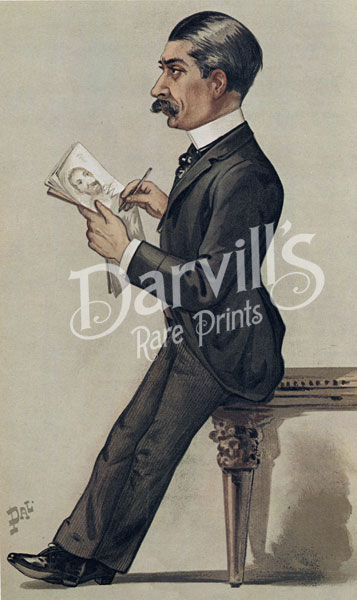

(excerpts from In 'Vanity Fair' This book is widely regarded as the authoritative source of information about Vanity Fair magazine. We highly recommend it for your further edification. Many public libraries contain the volume. Sadly, it is now out of print and getting difficult to obtain a copy for purchase. Ocassionally a copy can be found on eBay or book dealer sites. Why "Spy"? The Vanity Fair caricatures have become widely know as "Spy" prints due to the 1325 caricatures drawn by Sir Leslie Ward, who was a fixture at Vanity Fair for over 40 years. Ward and editor Bowles picked the name "Spy" from the dictionary to become Ward's nom de crayon. Many also cite Ward's propensity for methodical study of his 'victims' for many hours before beginning preliminary sketches as the real reason the name "Spy" stuck.

Carlo Pellegrini ("Ape") also did caricatures for the magazine for over 20 years (approx. 333 cartoons), so the prints might have become know as "Ape" prints were it not for Leslie Ward! click here for a complete list of the artists of Vanity Fair |

Introduction: For nearly fifty years, from 1868 to 1914, Vanity Fair displayed its political, social and literary wares weekly for the nineteenth-century Pilgrim. Inviting its readers to recognize the vanities of human existence, the publication, through its original format, prose and coloured caricatures, became the envy and model of other Society magazines. The most successful Society magazine in the history of English journalism was the result of the guiding genius of its founder and editor, Thomas Gibson Bowles (1842-1922), set against a background of historical circumstances ranging from the more mundane — technological breakthroughs in printing and lithography — to the sublime, the British Empire at its height. Written by and for the Victorian and Edwardian establishment, Vanity Fair was the magazine for those "in the know." Members of the Smart Set delighted in finding themselves caricatured in prose and picture. For them, Vanity Fair summarized each week the importanty events of their world. It reviewed the newest opening in the West End and the latest novel in the club's library; it aroused their curiosity and envy; it angered and amused them. The news and Society columns, the book and play reviews, the serialized novels and word games and the colour lithograph caricatures give us a glimpse into the lives and reputations of men and women who achieved either lasting or fleeting fame and fortune during the heyday of the British Empire. The caricatures, which have become the magazine's chief legacy, fascinate the scholar, the lay person and the collector for their historical and biographical value and their satirical and artistic quality. Although Vanity Fair is best remembered for these chromolithographic caricatures, the magazine was, at its zenith, recognized and respected in its totality — for its features, prose, advertising and format. The Caricatures: Vanity Fair's reputation and legacy have not rested exclusively on its political views, weekly columns, special articles and its prose style. Its popularity in the nineteenth century and its influence on British journalism are in no small part to be attributed to the caricatures. Like all other features in Vanity Fair, they were conceived by Bowles who, in early 1869, brought to his struggling magazine an unprecedented design and style of colour illustrations. On 16 January 1869, Bowles announced that since the literary offering of Vanity Fair had received so much favour, it was now proposed 'to add to them some Pictorial Ware of an entirely novel character.' Two weeks later, on 30 January 1869, the now famous caricature of Disraeli appeared, the first of over 2300 caricatures published in Vanity Fair. It was drawn by Carlo Pellegrini, using the nom de crayon 'Singe,' which he shortly thereafter angilicized to 'Ape.' Gladstone came next, followed by numerous dignitaries, including foreign Royalty, Earls, Lords, Bishops, politicians and a few women of social position or notoriety. This list was later extended to include such diverse characters as judges, journalists, criminals, sportsmen, artists, actors and Americans. At first some people were reluctant to be seen in the pages of Vanity Fair. However, as the popularity of the caricatures grew, they became less hesitant. In succeeding years, it became a mark of recognition to be the 'victim' of one of the caricaturists hired by Bowles. While most of the subjects took their turns with good grace, there were, of course, exceptions. Some, like Lewis Carroll, a close personal friend of Leslie Ward's (Spy) family, simply refused to pose. Carroll begged to be excused, saying that 'nothing would be more unpleasant for me that to have my face known to strangers.' Carroll's reaction can be attributed to his eccentricities or modesty. Delane, the editor of The Times, did not want to be caricatured, and asked William Howard Russell (Vanity Fair, 6 January 1875) to intervene for him with Bowles: 'The coin to bribe him with is a review of his book upon the Seige of Paris (sic) which he shall have if he will forgo his wicked will upon my poor face and figure.' Others, perhaps less eccentric than Carroll, were certainly displeased when the appeared in Vanity Fair. An amusing but innocuous sketch of the whysician, Dr. William Broadben, in 1902, led to his protest in The Lance, the medical journal, that he had been made to 'appear extremely ridiculous.' Vanity Fair, in characteristic manner, apparently failed to understand why Dr. Broadbent had interpreted the honour of being placed among so many distinguished subjects as an 'indignity.' Furthermore, Vanity Fair contended it was of no possible interest whether or not Sir William objected to the caricature. Earlier, Anthony Trollope had been exceedingly disturbed by his appearance in Vanity Fair. Spy and Trollope were invited to the house of a mutual friend, and after returning home, Ward sketched the novelist. The caricature, one of Ward's earliest works, appeared on 5 April 1873. Trollope, according to Ward, was incensed and especially angry over Spy's emphasis of Trollope's right thumb. John Pope Hennessy judged the caricature 'most unflattering' and said that it made Trollope look like 'an affronted Santa Claus.' Yet Pope Hennessey admitted, as did a majority of Trollope's contemporaries, that to have one's caricature in Vanity Fair was 'public honour no emminent man could well refuse.' During Vanity Fair's heyday, few emminent people refused this 'public honour,' for to be caricatured in Vanity Fair was to receive the recognition, if not always approbation, of England's leading Society magazine. click here to go to Darvill's Rare Prints Vanity Fair "Spy" Prints home page

|

|